#fragile: Feminist Revisionist Agile

In talks presented in Melbourne and Sydney this August, Portable COO Sarah Kaur presented a feminist revisionist interpretation of Agile. In Twitter discussion following the talks, the hashtag ‘#fragile’ (for ‘feminist revisionist Agile’) was swiftly adopted by attendees inspired by Kaur’s timely analysis. Here, we catch up with Kaur to learn why the future of Agile looks to be #fragile.

Kaur considers why the promise of Agile – a methodology the Harvard Business Review had hailed as “the competitive advantage for a digital age” – now appears to be breaking. “It’s not enough for us to say that Agile is ‘wrong,’” Kaur explains. “In order for Agile to be healthy in 10-20 years’ time, it must be worked on to ensure its great aspects remain.”

“If Agile is broken, let’s interrogate its structures,” continues Kaur. Using the lens of intersectional feminism, Kaur deconstructs the foundations of the Agile Manifesto. “Agile is influencing how the corporate world runs its projects. The time is now to unpack it and see how we can make it better!”

Why Feminism?

Intersectional feminism is built on the premise of interrogating established structures and unpicking their inherent assumptions —making it a useful tool to uncover why Agile isn’t working for everyone. This mode of analysis also accounts for the complex intersections that make up a contemporary workplace, where greater diversity exists in our staff, in our working hours and in the channels of communication available to us.

As Kaur points out, much has changed since the Agile Manifesto was written back in 2001. While those who wrote the Manifesto “would have had some differences – some were Scottish, some were American, some were Vietnam vets, some were aeronautical engineers – they were all pretty privileged, and kind of homogenic in comparison to today’s workforce.”

Portable’s all-women production team stands in stark contrast. Half the team is non-Caucasian, half are migrants to Australia. All are feminists. “The Agile Manifesto asks us to embrace that things change,” Kaur tells us. The Portable team believes feminism can effect this change, as “feminist thinkers have been remodelling the world around us… for a long, long time.”

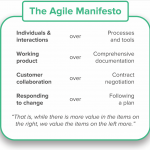

Central to Kaur’s analysis is the unpacking of the binary oppositions contained within the Agile Manifesto  Kaur doesn’t demand that we totally discard the items on the left. Indeed, she accepts that ‘responding to change’ is a far better way of working than ‘following a plan’. Yet, informed by feminism’s call to question opinions purporting to be objective truths, Kaur examines the often-overlooked value of the items on the right.

Kaur doesn’t demand that we totally discard the items on the left. Indeed, she accepts that ‘responding to change’ is a far better way of working than ‘following a plan’. Yet, informed by feminism’s call to question opinions purporting to be objective truths, Kaur examines the often-overlooked value of the items on the right.

Processes and Tools before Individuals and Interactions

Individuals and interactions are important but, Kaur notes, we need defined processes. “As the casualisation of the workplace increases, we rely more on a shared understanding of processes and tools to keep us aligned over remote and part-time work arrangements. How does your mum participate in a sprint when she’s working part-time?” Kaur asks. “It’s hard!”

As we’ve learned from cultural feminism, women are often responsible for maintaining social processes and tools; many of which are informal and, as such, are usually taken for granted. Women can be seen to act as a ‘gel’ or ‘social lubricant’, ensuring things like communication and relationship building run smoothly. This soft work is, in its own way, a process. “It’s always the little things,” Kaur explains, “comforting a colleague, remembering the birthdays, soothing an ego, showing a new employee the ropes. But these little things add up —and, for many women at work, they’re fed up.”

Kaur contends that tools and processes necessarily pave the way for interactions between individuals. Their role in the smooth functioning of a workplace can no longer be downplayed.

Comprehensive Documentation for Working Software

“Documentation is a form of democratising knowledge sharing,” says Kaur. “In tech especially, knowledge is power.”

The authors of the Agile Manifesto were pair programmers, meaning working code was easily comprehensible to them. But – fast forward to the present day – what happens when your developer goes on holiday? Work doesn’t stop. Your client asks you a question, and only your developer holds the answer. At the time the Manifesto was written, Kaur explains, “no one really had to understand these answers, bar those who were thinking the same. Why slow down and document stuff?”

As the above scenario illustrates, this rejection of comprehensive documentation doesn’t ‘work’ for everyone. It creates and maintains gaps in knowledge. It makes daily tasks needlessly complicated, particularly as the tech industry grows to encompass a broad spectrum of roles and skill levels. For Kaur, the question is raised: “who defines what ‘working’ means, and for whom does it ‘work’?”

Kaur argues that “knowledge shouldn’t be held in pockets of individuals’ heads.” Instead, we should document our processes in a shareable, easily comprehensible and teachable manner. Not only will this documentation simplify client communication; it could also serve as a valuable learning resource, allowing more people to access and contribute to these gated areas of discussion.

Contract Negotiation to pave the way for Customer Collaboration

“Contracts don’t work well with Agile,” Kaur tells us. Regardless of your work environment, there will always be someone (a client, a stakeholder, a third party provider, anyone!) who will require something.

Here, contract negotiation becomes critical. Kaur frames contract negotiation as an invaluable way to find out more about your partner: their expectations, their approaches and their non-negotiables. Trust is also built during the negotiation stage. “We’ve all heard that women are ‘good at compromising,’” Kaur laughs, referencing the “barbed compliment” that so many women receive. “Well, let’s turn this to our advantage!”

Kaur urges us to “reject the perception that women cannot negotiate.” Rather, she suggests that the negotiation process itself is flawed. Kaur draws on a Sheryl Sandberg quote: “People think that women don’t negotiate because they’re not good negotiators, but that’s not it. Women don’t negotiate because it doesn’t work as well for them.”

Kaur proposes that we make an effort to include women in contract negotiation from the outset, rather than merely having them step in when a ‘skilled compromiser’ is needed. Further, Kaur stresses the importance of women’s participation in the negotiation stage “so that we’re not bound to what someone else has decided are the rules.” If women are in the room when these negotiations take place, they can minimise harm and dismiss unreasonable conditions. Focusing solely on customer collaboration can exclude too many voices from the discussions that shape a project.

By framing negotiation as underserved by the Agile Manifesto – and as a forum that women can contribute to and reshape – Kaur blurs the binary between contract negotiation and customer collaboration. In Kaur’s words, we then have space to “make collaboration a deliverable with equal work from both parties.”

A #fragile Future

This isn’t about gender. For Kaur, #fragile is about challenging the cultural power structures that make Agile messy and difficult for everyone. Power structures and binaries are inevitable in all aspects of business; be it a client-agency binary or a founder-investor binary. So long as equal negotiation is prioritised, Kaur believes Agile can be a helpful future method of both dealing with and disrupting these power structures.

Kaur has noticed that too much emphasis can be placed on “doing Agile ‘right’. This shuts down discussion and stops people from wanting to give Agile a go.” Rather than treating Agile as a Bible, Kaur encourages us to adopt a mix of whatever Agile flavours meet our tastes and needs. In Kaur’s opinion, the only truly universal keys to making Agile work are trust and open communication.

Kaur leaves us with words from Agile Manifesto author Bob Martin: “Think of the Manifesto as a call to action in a point of time, and not a script of how to behave. It was a moment, not an era.” As this moment passes and we move to the next, the philosophy of Kaur and her team guides us in creating an inclusive, future-proof Agile.

https://hbr.org/sponsored/2016/04/agile-practice-the-competitive-advantage-for-a-digital-age

2“Uncle Bob Martin: The Agile Manifesto, 15 years later,” TechBeacon, 9 March 2016.

https://techbeacon.com/uncle-bob-martin-agile-manifesto-15-years-later

Stay in the loop

To receive updates about AgileAus and be subscribed to the mailing list, send us an email with your first name, last name and email address to signup@agileaustralia.com.au.

0 Comments